Home-Hame-Дом-Dom

ETHER Guest Blog Post - April 2021: Home-Hame-Дом-Dom – Encountering Difference and Attempting to Create a Shared Feeling of Belonging, by Claire Needler

Home-Hame-Дом-Dom was a community engagement project that used culture and creativity to break down social barriers and create a feeling of community belonging. The project aim was ‘to facilitate deeper engagement between Eastern European migrant communities and indigenous communities’ in four towns in North-East Scotland. We worked with groups from diverse cultural, linguistic and socioeconomic backgrounds, and brought people together to try out arts-based activities, meet new people, and have conversations in an informal, friendly environment. The activities were designed to overcome loneliness and social isolation, and strengthen social bonds between and within different sectors of the population. We created spaces for encountering difference by inviting mixed groups of East European and Scottish people to come together.

In this blog, extracts from Narrative Inquiry interviews (Clandinin 2013) and project photographs illustrate our innovative, values-based approach. Over the course of the project we mediated these encounters in different ways:

Celebrating Difference

In a series of events co-produced with Scottish, Polish and Lithuanian organisations, we celebrated Burns’ Night by eating haggis, neeps and tatties, listening to Scots poetry and ceilidh dancing. We celebrated Tłusty Czwartek by eating Polish doughnuts and singing Polish folk songs. We celebrated Kaziuko mugė by eating cold, pink soup and listening to a Lithuanian choir. These three events foregrounded and celebrated difference, creating opportunities for large groups of people from different national backgrounds to come together and share cultural experiences.

Ceilidh dancing at the Burns’ Night Taste o Hame event

Members of the Polish-Scottish singing group teaching a folk song

Lithuanian wall display changing the linguistic landscape at the Kaziuko mugė event

Foregrounding shared experiences rather than focusing on difference

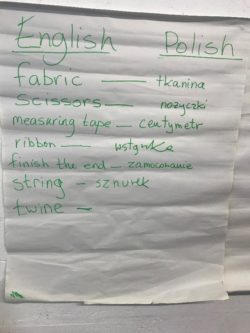

We ran a textile art workshop, in which a Polish artist and Scottish ESOL tutor co-facilitated the learning. This created an opportunity for people from different language backgrounds to come together and learn a new skill. The focus was on learning by doing, so all participants could engage with the task equally. We encountered difference through the language sharing that emerged during the event, but lack of proficiency in English or Polish was not a barrier to participation.

I must admit that I did not know what to expect before but I am very satisfied. The project is fantastic, combines pleasant with useful. You can learn about sewing in this case, but also practice English in a great company.

Participant feedback

Fig 1. Participants at the textile art taster session

Fig 2. English – Polish vocabulary collected during the workshop

All Differences Created Equal?

We worked in partnership with tutors from the communities we were trying to reach. In this example of good practice, communities had real ownership of the events, co-creating an innovative, experimental way of working together. However, we inadvertantly reinforced inequalities, rather than achieving the cultural equity that we intended. In the following interview extract, a majority Polish group switched to English to accommodate a single English-speaking participant.

Izabela: It was quite funny because there was only one English speaking, person who could speak only English, and the rest of us were Polish, and she [the Polish tutor] still had to do it in English [laughs].

Beata: So it was quite funny, we were all kind of breaking our tongues, for K to be in. It was funny. And it’s very interesting. I really liked this project.

Our approach is based on reciprocal ethnography (Lawless 2019) in that we recognise that we can all learn from each other, and by sharing our languages, our stories, and our lives with each other, we will all benefit from increased social connections (Ager & Strang 2008) and an increased feeling of belonging. Ralph and Staeheli (2011: 523) explain that ‘definitions of belonging are partly dependent on being recognised by others for their legitimacy’ and that ‘membership must be validated by the wider community or group to which one aspires to belong.’ In the encounter above, the Polish participants minimised their difference even though they were the majority.

Skillman (2020) suggests that many have argued that a sense of belonging is at the core of self-esteem. May (2011: 369) however, states ‘There exist […] hierarchies of belonging, and not everyone is allowed to belong.’ It took time and reciprocal emotional investment to build relationships with our community partners, based on an ethical and values-led approach. I shared my own stories and experiences of migration which helped to build trust, as seen here:

Gunta: I am a person who really would like to feel when people are coming together from different cultures, yes, I love them. Because there is no borders and no barriers, we are just people.

Claire: absolutely

Gunta: and it’s lovely to meet those people who think the same. As you! Yes, it’s really good, it’s really good.

Claire: You said to me once that you thought it would be hard to bring people from different countries together. Why did you think it would be difficult?

Gunta: Because adults are shy. To be open to other cultures because mainly they can’t speak English, or they can’t speak different language. This is the main thing I would say. Because adults, they would like to speak straight away in very good level. And when they can’t do it, then they are, then they can’t open themselves. This is the main reason I would say.

Often it was much easier for members of the host communities to encounter the Other than it was for the East Europeans to encounter the host community. As Gunta describes, lack of fluency in English meant that people couldn’t ‘open themselves’ and feel safe in these experimental places, whereas an English speaker with no Polish was accommodated when everyone switched to English. This shows up an unequal power relationship between our groups of participants, which would have needed more time to build relationships and establish trust within the groups to mitigate against hierarchical belonging, May (2001), as well as personal commitment and increased networking to develop this work further.

Nevertheless, bringing people together to share experiences, language, culture and food, created opportunities for meaningful engagement and ways of Seeing and Hearing the Other. At a local level, creating spaces for people to come together, begins to mitigate against the emotional impact of global challenges like Covid-19 and Brexit, and helped to create a feeling of community belonging.

References

Ager, A., and A. Strang. 2008. ' Understanding Integration: A Conceptual Framework', Journal of Refugee Studies, 21:2: 166-191 https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/fen016Clandinin, J.D. 2013. Engaging in Narrative Inquiry (Abingdon: Routledge)

Lawless, E. 2019. Reciprocal Ethnography and the Power of Women's Narratives (Bloomington: Indiana University Press)

May, V. 2011. ' Self, Belonging and Social Change', Sociology, 45(3): 363-378

McArdle, K. 2021. Home-Hame-Дом-Dom evaluation report https://www.abdn.ac.uk/elphinstone/documents/HHDD Report_final.pdf

Ralph, D., and L. Staeheli. 2011. 'Home and Migration: Mobilities, Belongings and Identities', Geography Compass, 5/7: 517-530

Skillman, A.E. 2020. 'Building Community Self-Esteem: Advocating for Culture', Folklore, 131:3: 229-243

Further Information

The Elphinstone Institute, University of Aberdeen, in partnership with the WEA and Modo, was commissioned by the North Aberdeenshire LEADER Local Action Group to deliver a £150k social integration project that used culture and creative arts to build links between people from different communities, especially those who have moved to the North-East for work. The North Aberdeenshire LEADER programme is part-financed by the Scottish Government and the European Community LEADER 2014-2020 programme.

Biography

Claire Needler is an Ethnology PhD student in the Elphinstone Institute, University of Aberdeen. She recently worked as the Project Co-ordinator on Home-Hame-Дом-Dom, a creative learning project that aimed to build a sense of community between migrants and host communities in small towns in the North-East of Scotland. She is particularly interested in the relationship between language, culture and education, and how they can interact to create a feeling of community identity and belonging. She uses creative methodologies and Participatory Action Research (PAR) in her work, always underpinned by a commitment to social justice.